HIKING WITH POETS

BY MIGUEL NEVES

I could see the red and yellow foliage in the distance as the landscape moved in synchronicity with the clanking of the train wheels on the track, making the mountains of Yamagata seem even more entrancing as they slowly passed the window giving way to more and more thickets of warm autumn colors. I had thoroughly researched my destination, a temple in the midst of a mountain range that seemed as full of soul as it had of filmic charm, good enough for 17th century poet Matsuo Basho to make a 7-mile detour from Obanazawa and climb the 1015 steps of this holy, yet tucked away place in the mountains.

Yamadera is located in the mountains of Yamagata province in the Tohoku region of Japan, a mere 30-minute train ride away northeast of Yamagata City. Yamaderas’ origins date back to the Heian Period and the temple was founded in 860 A.D. by the priest Jikaku Daishi who came back from studies in China in 854 A.D., becoming head priest of the Tendai sect of Buddhism. Its official name is Risshaku-ji, which literally means “standing stone temple” in Japanese.

I had high hopes and a deep craving for something that Basho used to describe this place in one of his most famous haikus: Such stillness, the cicadas’ cries, sink into the rocks. Stillness and silence were on my bucket list since I set foot in Japan, and Yamadera had the potential for me to indulge in some much-needed forest bathing, or as the Japanese call it, shinrin yoku, all amidst the silence that the woods can bring.

The wind had calmed down and I started heading towards the temple. Very few people were on temple grounds when I arrived at Sanmon Gate near the base of the temple. I expected such a famous place to be crowded and fast-paced with tourists, but I was mostly accompanied by couples or families that had travelled all the way here either to pay their respects or simply enjoy the maples and horse-chestnut trees turn colors. I walked away and kept an intentional distance from everyone whenever possible, the towering forest canopy was gradually enveloping me and the brushing of the wind against the leaves was creating a soundtrack that was impossible not to take in. My surroundings finally had my undivided attention.

All along the stairway, patches of moss covered the rocks next to Jizo statues, small stone figurines, donned with red caps and bibs, placed there purposefully to honor children that died ahead of time. The mixing of the green, the gray and the red elevates the forest into a realm of fantasy and otherworldliness, in a way that only the Japanese folklore can evoke. One of these particular spots is called the Semikuza mound, where Basho buried his poem, forever in rest in these woods, and in a way being the seed of magic that swathes Yamadera.

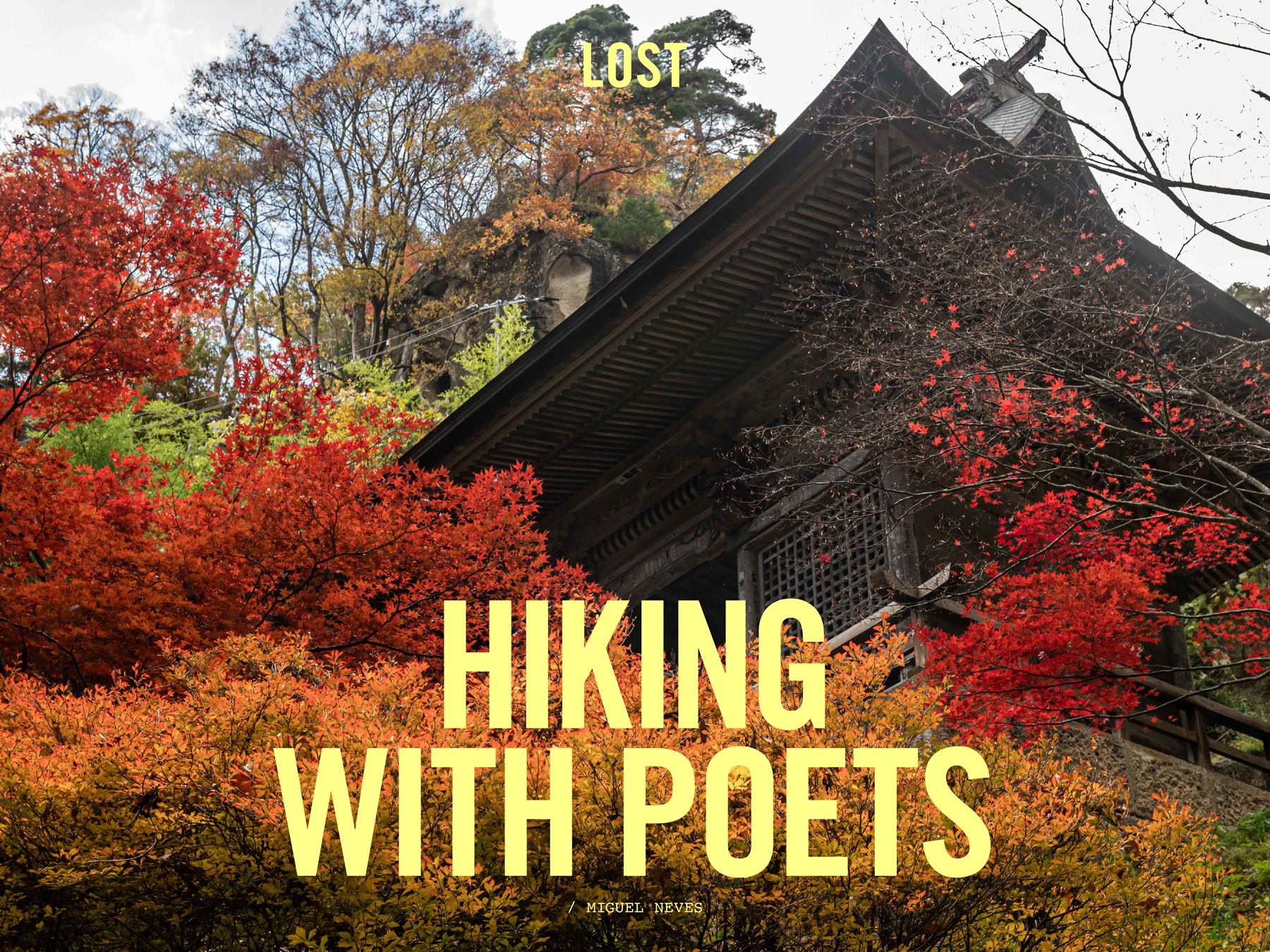

As I turned the corner of the stairs, I halted completely to admire a patch of orange and yellow etched in the foreground with a clouded sky as a backdrop, and in the middle, shily tucking in between the leaves and branches of the maple trees, was the Niomon Gate, one of the newest buildings in the complex dating to the 19th century and the marker that separates the lower and upper parts of the temple.

As I crossed it, I felt like I was being effectively transported to another realm, the landscape opened and I was finally above the canopy. Layers of mountain and forest stretched along the horizon, with the gold and green of the season cutting up a patch of color on the day’s gray skyline. It was only appropriate that a Buddhist temple would be sitting above the trees, as if it were a symbolic statement of the ascension towards communion with the Gods, and Yamadera certainly emanated that effect.

I took my last steps on the staircase passing the Kaizando and Nyohodo Halls, standing atop a cliff, dramatically framed on the landscape behind it and fitting the title as the postcard for Yamadera. The face of the hill that sided the temple grounds had a complete mystique of its own: trees clinging from the surface of the wall, branches pointing upwards crowned by yellow and red, and the Shakado temple entrenched in-between, asserting a kind of revering presence, driving my imagination to wonder what sorts of ceremonies might have been held at some point there. This scenery sparked more questions and wonder than any other part of the temple. It was like a resume of Yamadera put together, and a possible theme for a painting that shouldn’t go unmissed for anyone with an aesthetic sense.

But perhaps this is even more evident in the temples’ best-known viewpoint, the Godaido Hall, a scenic platform that dates back to the 1700’s. Enshrined here are the Godai Myo-o, the “Five Wisdom Kings, steadfast protectors of the Buddhism, and wrathful manifestations of Buddhas. As I approached the balcony I could finally materialize in my mind and senses the stillness that Basho spoke of as I peered towards the horizon painted with the autumn colours.

I arrived at the the upper part of the temple known as Okuno-in. The temple was rebuilt in 1872 and was used for coyping Sutras and it is said that Jikaku Daishi carried the principal images enshrined here, the Shaka Nyorai and the Taho Nyorai, all the way back from China. A couple of monks tended to the complex, sweeping the ground of dust and fallen leaves. They bore a solemn presence to them, seeming completely focused on the task at hand while I wandered through the temple grounds taking in as much of the small details as I could. Wooden plaques stacked on the rough gray wall of the mountain encircling a Jizo statue in-between them, the bell on the wooden tower probably used as a call for prayer, the graves that slope upwards into the hill and the dragon lantern imposing its’ presence with such intricate details.

I turned around and started the descent towards the train station. With my back turned to Okuno-in I was now standing in full appreciation of the glorious fire and golden leaves of Yamadera stretching along countryside. My trip to Japan was mostly motivated by this image, and atop these 1015 steps the brushstrokes of my mind came to fruition. Being this deep in nature and having the cultural and spiritual elements all present in the same place is, for me, the trifecta that makes travelling a priceless experience of observation and connection with the world. Yamadera caters to all senses, whether be it the silence between the ruffling of the trees shaken, the contemplation of every crevice and detail present in a Jizo Statue, or the taste of spicy Konnyaku balls topped with mustard served as you exit the these holy grounds, this complex deep in the Yamagata mountains has its unique aura and definitely worth the Basho-like detour you weren’t thinking of taking. Just remember to keep your ears open, lest you miss the cicadas’ cries.

MIGUEL NEVES is a photographer and writer based in Lisbon, Portugal whose work revolves around creating meaningful connections through photography while at the same time promoting self-discovery through travel. Follow his work on Instagram @thedeserts.